"Generally, the waters in the Arctic are less productive than Atlantic waters south of the Polar front", says Haakon Hop, Senior Researcher and head of ice ecosystems in the Centre for Ice, Climate and Ecosystems (ICE) at the Norwegian Polar Institute.

Algal bloom in the melt water

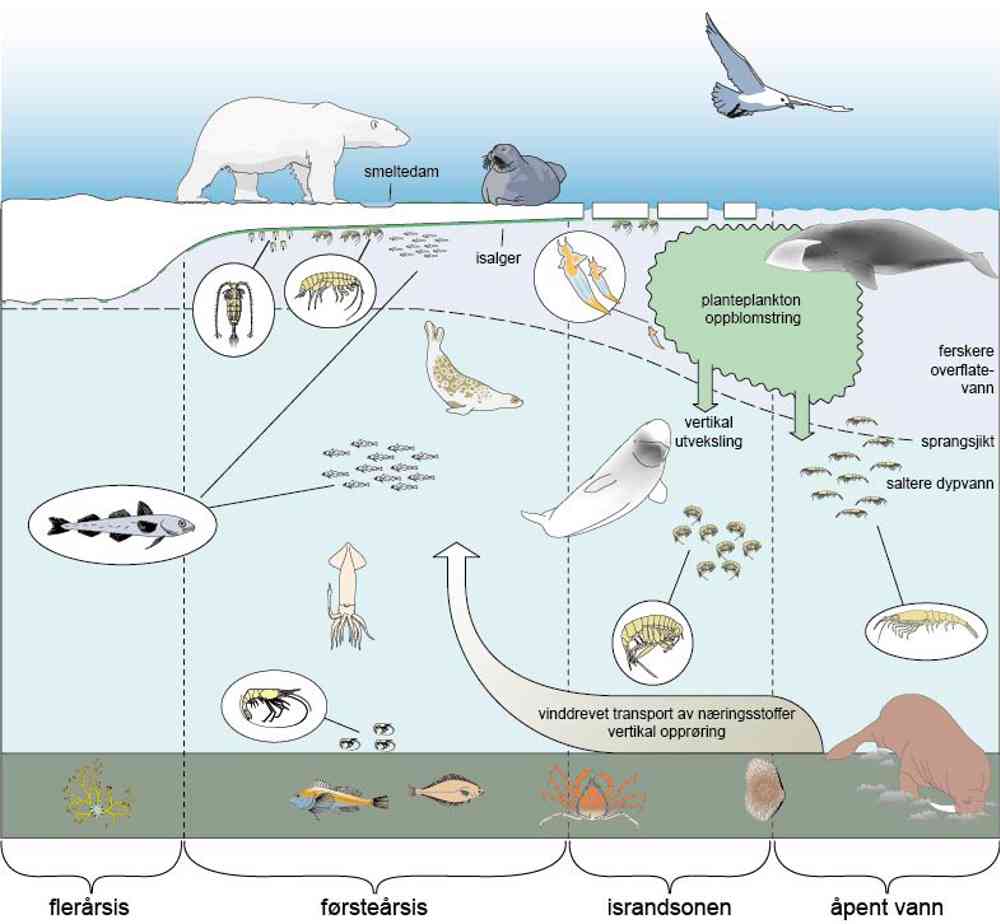

Phytoplankton is the foundation for animal life in the sea. In the spring, an algal bloom takes place. In order for that to happen, there must be a stratification of the water column. Such layers at depths of 20-30 meters are created by different saline contents or temperatures, and prevent the algae from sinking to depths were there is too little light to support plant growth. The stratification is created either by the surface water warming up or by melt water being added to the surface. The solar heating in the Arctic is too weak to create stratification, but when the sea ice melts the surface water near the ice edge becomes fresher than the salt water deeper down.

Nutrients are an another important condition for algal bloom. There are generally few nutrients in the Arctic sea, but autumn and winter storms churn the waters so that nutrient salts in the depths become available to algae further up. In the shallow Barents Sea, this churning reaches all the way to the seabed.

The ice edge

"When the ice edge melts northwards in the spring and summer, new areas are continuously becoming available for algal bloom. It lasts until all the nutrient salts have been consumed. This algal bloom along the ice edge thus becomes a productive band that moves further and further north over the course of the summer", says Hop.

Zooplankton feed on the algae at the ice edge, and zooplankton are in turn food for fish, sea birds and marine mammals. The ice edge is also where many seals rest and give birth, and where polar bears hunt seal.

Despite the teeming animal life, there is little commercial fishing along the ice edge.

When the sea ice melts in the spring, the ice edge becomes a rich area teeming with life. Illustration: Audun Igesund/Norwegian Polar Institute.

The ice retreats

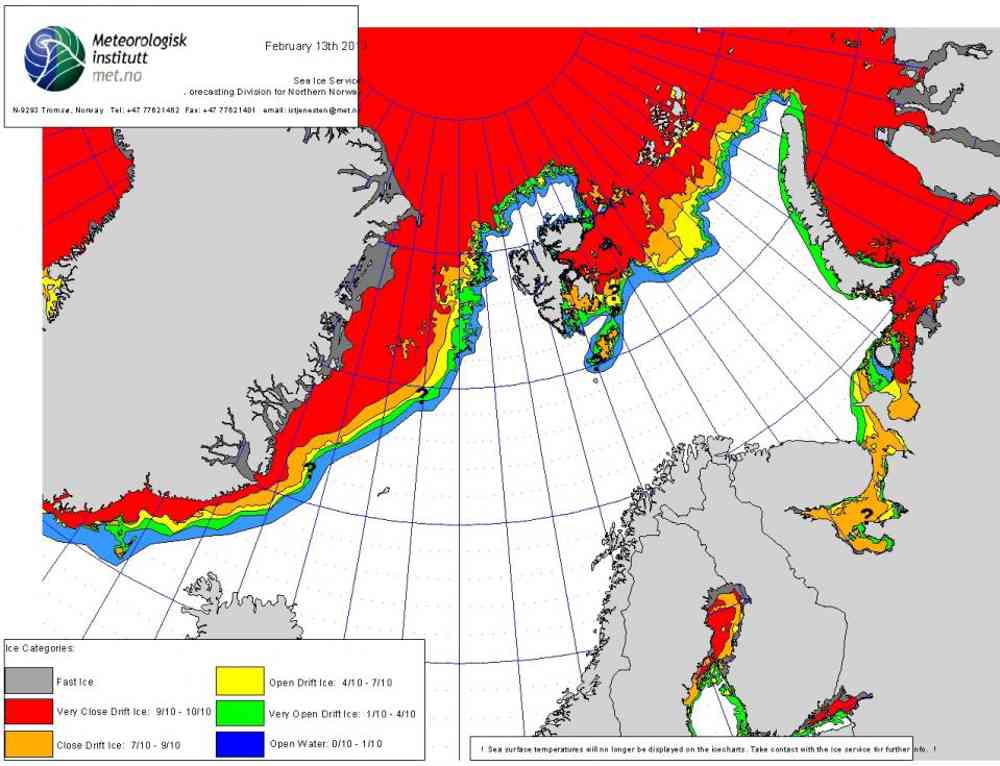

"The extent of the sea ice in the Arctic varies significantly through the year and from year to year", says Sebastian Gerland, the section leader for Oceans and Sea Ice at the Norwegian Polar Institute.

Since 1979, their measurements have shown a trend towards less and less sea ice in the Barents Sea.

All answers have not been found for why the sea ice is retreating. A warmer climate, with warmer air and water, naturally leads to shorter frost seasons and an earlier melting of the ice. However, several processes complicate the picture.

"As a starting point, the air is cold enough, and the water is cold enough to create sea ice. However, many factors such as sunlight, cloud cover, wind and ocean currents, water column stratification and ice dynamics affect this. Precipitation changes are also significant. For example, a thicker snow cover means that the sea ice grows slower", says Gerland.

Biological consequences

That the ice edge moves northwards affects animal life in the Arctic. The journey to feed at the ice edge can become too long for polar bears and sea birds.

"For birds nesting in Svalbard, it can become too far to fly from the nesting locations to the ice edge to find food. We are already seeing birds such as ivory gulls, kittiwakes and little auks preferring to graze in front of glaciers in Svalbard. Polar bears that remain on the mainland risk becoming very thin", says Haakon Hop.

According to Hop, it is not just in the Barents Sea that the ice edge has retreated northwards. In the East Siberian Sea, the sea north of central and eastern Siberia, the ice edge has retreated so far back that it has moved from the shallow continental shelf and out over the deep Arctic Ocean.

"When the ice edge is over the several thousand metre deep Arctic Ocean, the algae and nutrients disappear down to the bottom and out of the ecosystem. They are too far down to be reused the following year when the autumn and winter storms have churned the water masses, such as in the shallow continental seas. This has consequences for the biological production, which doesn't get very high", says Hop.

Pollution

The polar front, which is the border between warm Atlantic water and cold Arctic water, generally follows the ice edge at its maximum range in the eastern Barents Sea.

"Today, the ice-free part of the Barents Sea is important for the fisheries, with rich populations of cod, haddock and pollock. These are also important grazing areas for white-beaked dolphins and several species of baleen whales", says Jan Helge Fosså, Senior Researcher in the research group for benthic resources and processes in the Institute of Marine Research.

Parts of the Barents Sea have been opened for petroleum activity. If this is expanded to include areas with sea ice, this can cause environmental challenges.

"As a starting point, the problem related to oil is the same in the Arctic as it is for petroleum activities further south" says Harald Loeng, the Research Director in the Institute of Marine Research.

Though these are still hypothetical problems, he considers acute discharges such as a blowout or shipping accidents to be the greatest danger. If this occurs in the summer, it can affect algal bloom and the fish larvae. On the other hand, in the winter there is little biological production in the ice-covered areas.

"The question is which activity we want to permit in areas with a risk of sea ice", says Loeng.

The ice edge as of 13 February 2013.

According to Ann Mari Green, the chief engineer in the section for petroleum activities in the Norwegian Environment Agency, the ice edge is an ecosystem that is vulnerable to acute oil pollution, contaminants and climate change.

"The production of phytoplankton and zooplankton takes place at low temperatures in the upper layers of the ocean in a 20-50 km broad band along the ice edge. This means that the concentration of grazing species in the area can be high. This makes the ice edge vulnerable to acute oil pollution in parts of the year, especially for sea birds.

In addition to oil spills, she considers discharges of soot from combustion to be a problem. Soot is considered a short-lived climate driver, and will contribute to a faster global warming by increasing the melting of the ice. This affects the basis for the productive ecosystem.

Acute pollution at the ice edge comes with special challenges. This is not just because it takes place far from inhabited areas and infrastructure. Ice, and partly the darkness, makes it difficult to discover the pollution and makes the clean-up challenging. Booms and skimmers work poorly in an ocean full of ice. Chemical dispersal also has a limited effect because the ice dampens the waves that are necessary for the dispersants to mix with the oil. Incinerating the oil can be problematic because of the negative effects of the soot on the ice, but may nevertheless be the best alternative for removing oil from waters with sea ice.